Inferential Statistics

Summary of leaning objectives for each section

1 CLT and Sampling

1.1 Sampling Variability and CLT

1.1.1 Sample distribution and sampling distribution

-

Sample distribution: sample mean and sample variability (standard deviation)

-

Sampling distribution

population mean (\(\mu \)) and population standard deviation (\(\sigma\))

\[ \mu = \frac{x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_N}{N} \]

\[ \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N}(x_i - \bar{x})^2}{N}} \]

Most of time, population standard deviation \(\sigma\) is not known. Thus, \(\sigma\) is usually replaced by sampling standard deviation s

-

mean(\(\bar{x}) \approx \mu \)

-

standard error: \(SE = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\) < \(\sigma\)

-

The link to check up the shape of population distribution

1.1.2 Central Limit Theorem (CLT)

The distribution of sample statistics is nearly normal, centered at the population mean, and with a standard error equal to the population standard deviation divided by square root of the sample size.

\[ \bar{x} \sim N(mean = \mu, SE = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}) \]

\(N\) refers to the shape of distribution, meaning normal distribution.

\(\sigma\) is usually unknown, so s is used to replace \(s\) - sampling standard deviation

1.1.3 Other important concepts and rules

-

standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) vs. standard error (SE)

-

\(\sigma\) measures the variability in the data

-

SE measures the variability in the sample mean (point estimates)

-

-

sample size increases -> SE decreases (either from conceptual or mathematically \(SE = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\) point of view)

-

To reduce skewness, either increase sample size (observations) or number of samples

-

Sampling distribution will be nearly normal only if (the condition of CLT)

-

the sample size is sufficiently large (n ≥ 30 or even larger if the data are considerably skewed) or the population is known to have a normal distribution

-

the observations in the sample are independent: random sample/assignment and n < 10% of population if sampling without replacement

-

1.2 Confidential Intervals

1.2.1 Confidential Intervals

confidence interval is defined as the plausible range of values for a population parameter.

confidence level is defined as the percentage of random samples which yield confidence intervals that capture the true population parameter.

confidence interval for a population mean:

\[

\bar{x} \pm z\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}

\]

margin of error (ME) = \(z\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \)

- for 95% CI: \(\bar{x} \pm 2SE\) i.e., \(ME = 2SE\)

conditions for this confidence interval is the same as conditions for CLT (independent and sample size)

1.2.2 z-score (not covered in the course)

-

Given we know the population parameters (\(\mu\) and \(\sigma\)), calculate z-score for any individual in the population:

\[ z = \frac{(x - \mu)}{\sigma}

\]Using z-table, the probability can be calculated.

-

\[ z = \frac{(\bar{x} - \mu)}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}

\] -

Empirical rule

-

68% of values fall within 1 SE of the mean

-

95% fall within 2 SE of the mean

-

99% fall within 3 SE of the mean

-

1.2.3 Accuracy vs. Precision

-

Accuracy: whether or not the CI contains the true population paramter.

-

Precision: the width of a confidence intervals.

Increasing CL, accuracy increases but precision decreases.

- To get a higher precision and high accuracy - increase sample size

1.2.3 Required sample size for ME

\[ ME = z \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \rightarrow n = \Bigg(\frac{z s}{ME}\Bigg)^2 \]

1.3 R vs. sampling distribution

- Load the package and dataset(ames)

library(statsr)

library(dplyr)

library(shiny)

library(ggplot2)

data(ames)

- Distribution of areas of homes and summary statistics

ames %>%

summarise(mu = mean(area), pop_med = median(area),

sigma = sd(area), pop_iqr = IQR(area),

pop_min = min(area), pop_max = max(area),

pop_q1 = quantile(area, 0.25), # first quartile, 25th percentile

pop_q3 = quantile(area, 0.75)) # third quartile, 75th percenti

- Sample randome 50 houses and calculate the average area

samp1 <- ames %>%

sample_n(size=50)

samp1 %>%

summarise(x_bar = mean(area))

# or combine above two code chunks into one

samp1 <- ames %>%

sample_n(size=50) %>%

summarise(x_bar = mean(area))

- Estimate population mean by using sampling distribution

Take 15,000 samples of size 50 from the population (rep_sample_n), calculate the mean of each sample, and store each result in a vector called 'sample_means50'.

sample_means50 <- ames %>%

rep_sample_n(size = 50, reps = 15000, replace = TRUE) %>%

summarise(x_bar = mean(area))

ggplot(data = sample_means50, aes(x = x_bar)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 20)

To get the summary statistics of 15,000 sample means, analyze the statistics from the 'sample_means50', which is actually a dataset containing 15,000 observations(x_bar).

sample_means50 %>%

summarise(sampling_x_bar = mean(x_bar))

1.4 Python vs. sampling distribution

- Load packages and import dataset

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import random as random

import math

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ames = pd.read_csv("/content/drive/MyDrive/Colab Notebooks/ames.csv")

#ames.head

#ames.columns

- Distribution of population

mu = np.average(ames["Lot.Area"])

sigma = np.std(ames["Lot.Area"])

plt.hist(ames["Lot.Area"],30, range=[0, mu+5*sigma])

plt.show()

#right skewed distribution

- Randomly take 10 samples

samp1 = ames.sample(n=10,replace=True)

- Take 1000 samples with size 200

size = 200

num_samp = 1000

samp_mean = []

for m in range(num_samp):

samp = ames.sample(n=size,replace=True)

x_bar_samp = np.average(samp["Lot.Area"])

samp_mean.append(x_bar_samp)

m += 1

x_bar_samp_mean = np.average(samp_mean)

x_bar_samp_se = np.std(samp_mean)/(math.sqrt(size))

print(x_bar_samp_mean)

print(x_bar_samp_se)

plt.hist(samp_mean, 20, range=[5000,15000])

plt.show()

2 Hypothesis testing and significance

2.1 Hypothesis testing (for a mean)

-

Null hypothesis - \(H_0\)

-

Alternative hypothesis - \(H_A\)

The hypothesis is always about pop.parameters, never about sample statistics (because the sample statistics is certain).

-

p-value - P(observed or more extreme outcome | \(H_0\) true)

Given \(n = 50, \bar{x} = 3.2, s = 1.74, SE = 0.246\)

We are looking for \(P(\bar{x} > 3.2 | H_0 : \mu = 3) \)

Since we believe that null hypothesis is true, \(\bar{x} \sim N(\mu = 3, SE = 0.246)\) based on the CLT.

test statistics: z-score = (3.2-3)/0.246 = 0.81, which is used to calculate the p-value (the probability of observing data at least favorable to the alternative hypothesis as our current data set, if the null hypothesis was true)

p-value = P(z > 0.81) = 0.209

Decision based on the p-value

-

p-value < the significant level, \(\alpha\) (usually 5%): it is unlikely to observe the data if the null hypothesis is true: Reject \(H_0\)

-

p-value ≥ \(\alpha\): it is likely to occur even if the null hypothesis were true: Do no reject \(H_0\)

two-sided(tailed) tests

In the same case, \(P(\bar{x} > 3.2 \text{ or } \bar{x} > 2.8| H_0 : \mu = 3) \)

p-value = \(P(z > 0.81) + P(z < -0.81) = 0.418 \) --- fail to reject \(H_0\).

2.2 Significance

2.2.1 Inference for other estimators

-

point estimates:

\(\hat{\theta}\): \(\hat{\theta}_{LMS}\) or (\(\hat{\theta} _{MAP}\)) the concept might be different from MIT statistics course

-

sample mean

-

difference between sample means

-

sample proportion \(\hat{p}\)

-

difference between two proportions

-

-

two requirements:

-

nearly normal sampling distribution

-

unbiased estimator assumption: point estimates are unbiased, i.e., the sampling distribution of the estimate is centered at the true population parameter it estimates.

-

2.2 Decision errors

Decrease significance level (\(\alpha\)) decrease Type I error rate

\(P(\text{Type I error}|H_0 \text{ true}) = \alpha\)

-

Choosing \(\alpha\)

-

if Type I error is dangerous or costly, choose a small significance level (e.g. 0.01)

-

if Type II error is dangerous or costly, choose a high significance level (e.g. 0.10)

-

\(\beta\) depends on the effect size \(\delta\) - difference between point estimate and null value.

2.2.3 Significance level vs. confidence level

-

complement each other depending on one-sided or two -sided tests

- two-sided tests: Significance level = 1 - confidence level

-

one-sided tests: Significance level ≠ confidence level

CL = 1 - 2 x alpha

2.2.4 Statistical vs. practical significance

-

practical significance

Real difference between point estimator and null value are easier to detect with larger samples (effect size)

-

statistical significance

very large samples will result in statistical significance even for tiny differences between sample mean and the null value (effect size), even when the difference is not practically significant.

3 Inference for Comparing Means

3.1 t-distribution and comparing two means

3.1.1 t-distribution

What purpose does a large sample serve?

As long as observations are independent, and the population distribution is not extremely skewed, a large sample would ensure that

-

the sampling distribution of the mean is nearly normal.

-

the estimate of the standard error is reliable: \(\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\)

t-distribution

-

when σ unknown(almost always), use the t-distribution to address the uncertainty of the standard error estimate

-

bell shaped but thicker tails than the normal

-

observations more likely to fall beyond 2 SDs from the mean

-

extra thick tails helpful for mitigating the effect of a less reliable estimate for the standard error of the sampling distribution

-

-

always centered as 0

-

only has one parameter degress of freedom(df) to determine the thickness of tails: higher df, less thick the tail

the normal distribution has two parameters: mean and SD

-

for inference on a mean where σ unknown, the calculation is the same way as normal distribution

\[ T = \frac{\text{obs - null}}{SE} \]

- find p-value (one or two tail area, based on \(H_A\))

3.1.2 Inference for a mean

estimating the mean = point estimate ± margin of error

\[ \bar{x} \pm t_{df}^*SE_{\bar{x}} \\ SE_{\bar{x}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \]

degrees of freedome for t statistic for inference on one sample mean

\[

df = n - 1

\]

3.1.3 Inference for comparing two independent means

estimating the mean = point estimate ± margin of error

\[ (\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}) \pm t_{df}^*SE_{(\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2})} \]

-

SE of difference between two independent means

\[ SE_{(\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2} )}= \sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}} \]

-

DF for t statistics for inference on difference of two means

\[ df = min(n_1-1, n_2-1) \]

-

Conditions for inference for comparing two independent means

- independence:

- within groups: - random sample/assignment - if samping without replacement, n < 10% of population - between groups: not paired- Sample size/skew: the more skew in the population distributions, the higher the sample size needed.

3.1.4 Inference for comparing two paried means

When two sets of observations have a special correspondence(not independent), they are said to be paired.

Two analyze paired data, it is often useful to look at the difference in outcomes of each pair of observations.

-

Parameter of interest: \(\mu_{diff}\) - average difference between the reading and writing scores of all high school students

-

Point estimate: \(\bar{x}_{diff}\) - average difference between the reading and writing scores of sampled high school students

-

\(SE = \frac{s_{diff}}{n}\)

Summary

-

paired data (2 var.) \(\to\) differences (1 var.)

-

most often: \(H_0:\mu_{diff} = 0\)

-

same individuals: pre-post studies, repeated measures, etc.

-

different but dependent individuals: tiwns, partners, etc.

3.1.5 Power

Power of a test is the probability of correctly rejecting H0, and the probability is \(1-\beta\)

- Practical problem 1: calculate power for a range of sample sizes and choose target power

- Practical problem 2: calculate required sample size for a desired level of power

3.2 ANOVA and Bootstrapping

3.2.1 Comparing more than two means -- F distribution

ANOVA (analysis of variance) test

-

\(H_0\): the mean outcome is the same across all categories

-

\(H_A\): at least one pair of means are different from each other

| t-test | ANOVA |

|---|---|

| compute a test statistic (a ratio) | Compute a test statistic (a ratio) |

| \[t = \frac{(\bar{x_1}-\bar{x_2})-(\mu_1-\mu_2)}{SE_{(\bar{x_1}-\bar{x_2})}}\] | \[F = \frac{\text{variability bet. groups}}{\text{variability within groups}}\] |

-

In order to be able to reject \(H_0\), we need a small p-value, which requires a large F statistic.

-

Obtaining a large F statistic requires that the variability between sample means is greater than the variability within the samples.

3.2.2 ANOVA

-

variability partitioning

-

ANOVA Output

ANOVA Output table

-

The first row is about between group variability (Group row) and the second the row is the within group variability (Error row)

-

Sum square error

- Total: sum of squares total (SST) measures the total variability in the response variable. The caculation is very similar to that of variance except for no dividing by the sample size. \\[ SST = \sum\limits_{i=1}^n (y_i-\bar{y})^2 \\] \\(y_i\\): value of the response variable for each observation \\(\bar{y}\\): grand mean of the response variable - Group: sum of squares groups (SSG) measures the variability between groups. <u>Explained variability</u>: squared deviation of group means from overall mean, weighted by sample size. \\[ SSG = \sum\limits_{j=1}^k n_j(\bar{y_j}-\bar{y})^2 \\] \\(n_j\\): number of observations in group *j* \\(y_j\\): mean of the response variable for group *j* \\(\bar{y}\\): grand mean of the response variable - Error: sum of squares error (SSE) measures the variability within groups. <u>Unexplained variability</u>: unexplained by the group variable due to other reasons \\[ SSE = SST - SSG \\]-

DF: degree of freedom

-

Mean square error: average variability between and within groups, calculated as the total variability (sum of squares) scaled by the associated degrees of freedom.

-

group: MSG = SSG/DFG

-

error: MSE = SSE/DFE

-

-

F statistics: ratio of the average between group and within group variabilities

\[ F = \frac{MSG}{MSE}

\] -

Calculate p-value according to F statistics, and remember F always positive we only calculate one-tail.

-

if p-value is small (less than \(\alpha\)): reject H0

The data provide convincing evidence that at least one pair of population means are different from each other (but we cannot tell which one)

-

if p-value is large (larger than \(\alpha\)): fail to reject H0

The data do not provide convincing evidence that at least one pair of population means are different from each other; the observed difference in sample means are attributable to sampling variability (or chance)

-

-

3.2.3 ANOVA conditions

-

Independence: between groups and within groups

-

Approximate normality: distributions should be nearly normal within each group

-

constant variance: groups should have roughly equal variability

side-by-side boxplot is helpful to check constant variance condition

3.2.4 Multiple comparisons

-

Bonferroni correction: adjust \(\alpha\) by the number of comparison being considered K

\[ K = \frac{k(k-1)}{2} \\ \alpha^* = \alpha/K

\] -

Pairwise comparisons:

-

constant variance \(to\) use consistent standard error and degrees of freedom for all tests

-

compare p-values from each test to the modified significance level

-

Standard error for multiple pairwise comparisons:

\[ SE = \sqrt{\frac{MSE}{n_1}+\frac{MSE}{n_2}} \]

compared to t test between two independent groups \(SE = \sqrt{\frac{S_1^2}{n_1}+\frac{S_2^2}{n_2}}\)

-

Degrees of freedom for multiple pairwise comparisons: df = dfE

compared to t test: df = min(n1 - 1, n2 - 1)

-

3.2.5 Bootstrapping

-

Bootstrapping scheme:

-

take a bootstrap sample - a random sample taken with replacement from the original sample, of the same size as the original sample

-

calculate bootstrap statistic - mean, median, proportion, etc. computed on the bootstrap samples.

-

repeat steps 1 and 2 many times to create a bootstrap distribution - a distribution of bootstrap statistics.

-

-

calculate confidence interval:

-

percentile method

-

standard error method

-

-

limitations

-

not as rigid conditions as CLT based methods

-

if bootstrap distribution is extremely skewed or sparse, the bootstrap interval might be unreliable

-

A representative sample is still needed - if the sample is biased, the estimates resulting from this sample will also be bias.

-

Bootstrap vs. sampling distribution

-

sampling distribution: created using sampling with replacement from the population

-

Bootstrap distribution: created using sampling with replacement from the sample

-

Both are distributions of sample statistics

4 Inference for Proportion

Categorical variables oppose to numerical variables

-

one categorical variable:

-

two levels: success-failure

-

more than two levels

-

-

two categorical variables:

-

two levels: success-failure

-

more than two levels

-

4.1 Inference for proportions

4.1.1 Sampling Variability and CLT for Proportions

For numerical variables, sample statistic from sampling distribution is mean

For categorial variables, sample statistic from sampling distribution is proportion

CLT for proportions: The distribution of sample proportion is nearly normal, centered at the population proportion, and with a standard error inversely proportional to the sample size.

\[ \hat{p} \sim N \left( mean=p, SE=\sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}}\right) \]

-

Conditions for the CLT

-

Independence

-

Sample size/skew: there should be at least 10 successes and 10 failures in the sample: np ≥ 10 and n(1-p) ≥ 10.

-

-

What if the success-failure condition is not met:

-

the center of the sampling distribution will still be around the true population proportion

-

the spread of the sampling distribution can still be approximated using the same formula for the standard error

-

the shape of the distribution will depend on whether true population proportion is close to 0 (righ skew) or to 1 (left skew).

-

4.1.2 Confidence interval for a proportion

-

parameter of interest: \(p\)

-

point estimate: \(\hat{p}\) sample proportion

-

estimating a proportion: point estimate ± margin of error

\[ \hat{p} = z^* SE_{\hat{p}}

\]-

SE for a proportion for calculating a confidence interval:

\[ SE_{\hat{p}} = \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}(1-\hat{p})}{n}} \]

-

calculating the required sample size for desired ME

-

use \(\hat{p}\) from previous study

-

if no previous study, use \(\hat{p} = 0.05\) as it gives the most conservative estimate - highest possible sample size

-

-

4.1.3 Hypothesis testing for a proportion

-

set the hypothesis

-

calculate the point estimate \(\hat{p}\)

-

Check conditions

-

Draw sampling distribution, shade p-value, calculate test statistic.

-

Make a decision based on the research context.

Null hypothesis always contains a "=" sign.

4.1.4 Estimating the Difference Between Two Proportions

calculating a confidence interval for the difference between the two population proportions that are unknown using data from our sample

-

Estimating the difference between two proportions:

\[ (\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p} _2) \pm z^* SE _{(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2)} \\ SE = \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}_1(1-\hat{p}_1)}{n_1} + \frac{\hat{p}_2(1-\hat{p}_2)}{n_2}}

\] -

conditions for inference for comparing two independent proportions

-

Independent: within groups and between groups

-

Sample size/kew: each sample should meet the success-failure condition

-

4.1.5 Hypothesis Test for Comparing Two Proportions

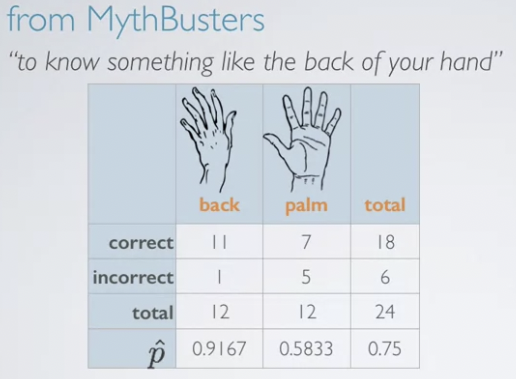

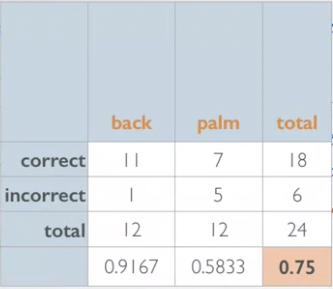

pooled proportion \(H_0: p_1 = p_2 = \) pooled proportion

\[

\hat{p}_{pool} = \frac{\text{total successes}}{\text{total n}}

\]

4.2 Simulation based inference for proportions and chi-square testommg

4.2.1 Small sample proportion

which does not meet success-failure condition

-

inference via simulation

-

setting up a simulation assuming H0 true

-

the ultimate goal of a hypothesis test is a p-value

-

devise a simulation scheme that assumes the null hypothesis is true

-

repeat the simulation many times and record relevant sample statistic CLT?

-

calculate p-value as the proportion of simulations that yield a result favorable to the alternative hypothesis

-

4.2.2 Comparing Two Small sample proportions

For comparing two proportions with hypothesis test, the pooled proportion should be used.

4.2.3 Chi-Square GOF test

Deals with data with one category with more than two levels to a hypothesis distribution

-

Conditions for the Chi-Sqaure test:

-

Independence

-

random sample/assignment

-

if sampling without replacement, n < 10% of population

-

each case only contributes to one cell in the table

-

-

Sample size: each particular scenarior (i.e., cell) must have at least 5 expected cases.

-

-

Anatomy of a test statistic

General form of a test statistic

\[ \frac{\text{point estimate - null value}}{\text{SE of point estimate}}

\]-

identifying the difference between a point estimate and an expected value if the null hypothesis were true

-

standardizing that difference using the standard error of the point estimate

-

-

Chi-Square \(\chi\) statistic: dealing with counts and investigating how far the observed counts are from the expected counts

\[ \chi^2 = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{k}\frac{(O-E)^2}{E}

\]O: observed

E: expected

k: number of cells

-

Chi-Square \(\chi\) distribution: has just one parameter

- degrees of freedom (df): influence the shape, center and spread

-

p-value

-

p-value for a chi-square test is defined as the tail area above the calculated test statistic

-

the test statistic is always positive, and a higher test statistic means a higher deviation from the null hypothesis

-

4.2.4 Chi-Square independence test

Deals with two categorial variables at least one with > 2 levels

Chi-square independence test is to evaluate the relationship between two categorical variables

\[

\chi^2 = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{k}\frac{(O-E)^2}{E}

\]

-

df = (#rows - 1)x(#columns - 1)

-

the same conditions as chi-square GOF test

4.3 Assumption consistency

One Population Proportion

-

Sample can be considered a simple random sample

-

Large enough sample size ()

-

Confidence Interval: At least 10 of each outcome ()

-

Hypothesis Test: At least 10 of each outcome ()

-

-

-

Two Population Proportions

-

Samples can be considered two simple random samples

-

Samples can be considered independent of one another

-

Large enough sample sizes ()

-

Confidence Interval: At least 10 of each outcome ()

-

Hypothesis Test: At least 10 of each outcome () - Where (the common population proportion estimate)

-

-

-

One Population Mean

-

Sample can be considered a simple random sample

-

Sample comes from a normally distributed population

- This assumption is less critical with a large enough sample size (application of the C.L.T.)

-

-

One Population Mean Difference

-

Sample of differences can be considered a simple random sample

-

Sample of differences comes from a normally distributed population of differences

- This assumption is less critical with a large enough sample size (application of the C.L.T.)

-

-

Two Population Means

-

Samples can be considered a simple random samples

-

Samples can be considered independent of one another

-

Samples each come from normally distributed populations

-

This assumption is less critical with a large enough sample size (application of the C.L.T.)

-

Populations have equal variances – pooled procedure used

-

If this assumption cannot be made, unpooled procedure used

-

-

-